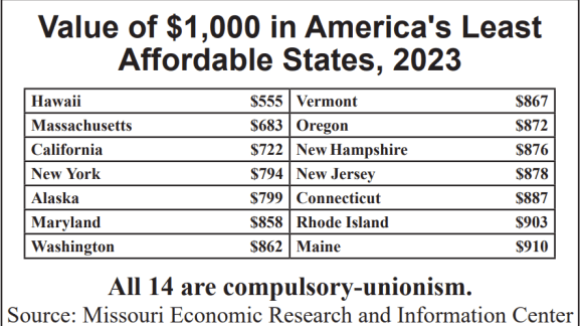

Banning Compulsory Dues Curbs Cost of Living

On average, forced-unionism states are 23.2% more expensive to live in than Right to Work states. And decades of academic research show that compulsory unionism actually fosters a higher cost of living.

With America in an economic downturn and big labor poised to make substantial electoral gains, it is critical to understand their agenda and the impact it will have on economic growth. National Right to Work President Mark Mix has done just that in the Wall Street Journal.

Revisionist historians like to claim that it was President Roosevelt’s policies that “led us from the great Depression.” But most economists now understand his policies actually prolonged it by over seven years. Part of the Roosevelt plan was enactment of the Wagner Act, a measure that authorized union officials to seek and obtain the power to act as the exclusive (that is, the monopoly) bargaining agent over all the front-line employees, including union nonmembers as well as members, in a unionized workplace.

Mix examines the history:

As Amity Shlaes observed in her recent history of the Great Depression, “The Forgotten Man,” within a few months after the Wagner Act was upheld, industrial production began to plummet and “the jobs started to disappear, with unemployment moving back to 1931 levels,” even as the number of workers under union control was “growing astoundingly.”

Given the reality of unions in the workplace, the law meant that efficiency and profitability were compromised, by forcing employers to equally reward their most productive and least productive employees. Therefore subsequent wage increases for some workers led to widespread job losses.

Pre-Depression-era growth and prosperity did not return to the private sector until the early 1950s, when the spread of state right-to-work laws prohibiting forced union membership and dues greatly reduced the detrimental effects of the Wagner Act.

The U.S. has just experienced another stock market crash, and Barack Obama, the candidate now favored to be the next president, is in favor of what amounts to a new Wagner Act.

If the mislabeled “Employee Free Choice Act,” becomes law, it will likely have a similar effect on the economy as the original Wagner Act, transforming what could have been a recovery into a lengthy, deep recession, or worse.

The bill would greatly facilitate organization in workplaces by effectively eliminating secret ballot elections, allowing unions to become exclusive bargaining agents when a majority of the workers sign a card indicating they want a union — before they’ve heard a word from their employer about the potential downside of unionization.

The cards themselves may be signed under duress. Service Employees International Union (SEIU) czar Andy Stern predicts that its enactment would cause unions to “grow by 1.5 million members a year, not just for five years but for 10 to 15 straight years.”

Sen. Obama voted for one version of the card-check bill in June 2007 and pledged to Big Labor that he will push for enactment as president. With a handful of pickups he will have a filibuster-proof majority in the next Senate, and can make good his pledge.

“I owe those unions,” Mr. Obama explained in his 2006 political memoir, “The Audacity of Hope.” “When their leaders call, I do my best to call them back right away. I don’t consider this corrupting in any way . . .”

John McCain voted against card-check legislation in 2007, and has pledged to veto such legislation as president. He also supports a national right-to-work law that would repeal all current federal labor law provisions authorizing forced union dues and fees. Unfortunately, his campaign has done little to alert the nation to the dangers of the card-check bill.

Before they cast their votes, the American people ought to be aware of Mr. Obama’s commitment to the passage of a new Wagner Act, and of what the economic consequences of such a law are almost certain to be.

History tends to repeat itself. In the question of the upcoming Big Labor power grab, the question is — will you let it?

On average, forced-unionism states are 23.2% more expensive to live in than Right to Work states. And decades of academic research show that compulsory unionism actually fosters a higher cost of living.

After union lawyers’ attempt to get the NLRB to block the vote failed, CWA union bosses backed down and departed AT&T workplace rather than face workers’ vote

Biden judicial nominee Nicole Berner has a track record of mindlessly repeating union bosses’ anti-Right to Work diatribes and defending their schemes to profit at the expense of the disabled.