Will Team Biden Weaponize Workers’ Pensions?

Big Labor abuse of worker pension and benefit funds as a means of advancing union bosses’ self-aggrandizing policy objectives is a familiar phenomenon.

The captivating legal drama of Marvin and Laura Horne continued last week as the case brought by these married California raisin farmers and handlers received an extraordinary second hearing before the U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday, April 22.

The Hornes are challenging the constitutionality of the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act (AMAA) of 1937 as it affects them and their business. They contend the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) cannot licitly collect accumulated bills and fine them for having refused for years to fork over a portion of their crop, a requirement authorized by the AMAA.

The AMAA empowers an elected board of bureaucrats known as the Raisin Administrative Committee (RAC) to issue “agricultural marketing orders” mandating that producers surrender a portion of their annual crop. How much handlers are required to surrender depends on the estimated size of the entire U.S. raisin crop in any given year.

The confiscated raisins are temporarily or permanently taken out of the commercial domestic market. The principal avowed goal of this program is to prevent “overproduction” that could drive down the price of raisins. Foreign sales of the raisins also raise money for domestic advertising programs for unbranded raisins.

Last week’s hearing in the Horne case basically focused on the question of whether the requirement that the Hornes hand over a portion of their raisins to the RAC in certain years, or give up their right to sell any raisins at all, violates the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (See the link below for a transcript.)

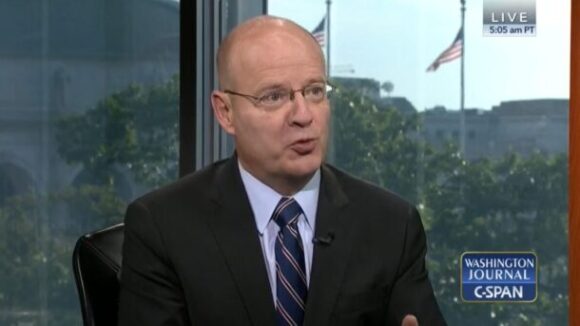

And a key argument made by Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler on behalf of the Agriculture Department and in defense of the AMAA at the hearing may well sound very familiar to freedom-loving Americans who have ever participated in or watched debates over the Right to Work issue.

Time and again, Kneedler emphasized that the RAC, the committee that decides whether or not to seize raisins, and how many will be seized, from producers each year is “elected by producers.” Roughly three-quarters of the way through the hearing, he suggested to a skeptical Justice Antonin Scalia that it is “important to recognize” this fact.

Scalia then opted to press the point. The producers elected the RAC members, and “so they can impose taxes, you’re saying. This is just like a tax.” Is that what Kneedler meant?

Kneedler rejected the description of marketing orders as a tax, but insisted they are defensible as a “regulatory program adopted by producers.”

But Scalia couldn’t see why other producers ought to have the power to make the decision on the Hornes’ behalf that a portion of the Hornes’ raisins should be handed over to the RAC.

“Whatever a majority of the producers agree to, I have to be bound by?” Scalia incredulously asked Kneedler. “I mean, these people disagree.”

Scalia, and probably most justices on the court today, understand that the Constitution does not normally authorize the majority of actors in a group to dictate to the minority how they should conduct their private affairs. But so far the court has not seen fit to apply this principle to federal labor policy.

Just as the AMAA empowers elected bureaucrats to confiscate raisins from farmers in order to prevent “too many” of them from being sold in the American private-sector marketplace, the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) and the Railway Labor Act (RLA) empower elected union officials to impose productivity-quashing work rules on union members and nonmembers alike. The aim of such work rules, in many cases, is to “protect” workers’ jobs by preventing them from producing too much, just as the RAC aims to keep raisin prices high by deterring farmers from growing too many.

Moreover, under the NLRA and the RLA, workers who may or may not think they benefit from work rules that keep them from being “excessively” productive are forced to fork over dues or fees to the union acting as their “exclusive” bargaining agent, just as the Hornes have been ordered to turn over a portion of their raisins to the RAC’s agents.

The actual intent of the collectivist economic measures of the 1930’s, as some sponsors of the NLRA’s immediate precursor, the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act, openly admitted, was to enable businesses to raise prices, and thus help them pay workers more. Similar, the scarcely disguised goals of the AMAA were higher food prices for consumers and higher profits for farmers.

Of course, in practice laws often have unintended consequences, and producers like the Hornes have good reasons to believe they would be better off with free competition than they are with the government’s heavy-handed “help.” Similarly, many employees have good reason to believe they benefit from the very competition union bosses seek to stop with restrictive work rules.

If, as a number of seasoned observers of the judiciary now expect, the High Court finds the AMAA as implemented to be unconstitutional as well as counterproductive, perhaps the days of the NLRA and the RLA may also be numbered.

6 days ago – Petitioner. : No. 14275. 5 v. : 6. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. … Laura Horne, and more indirectly, hundreds of small. 15. California raisin …

Big Labor abuse of worker pension and benefit funds as a means of advancing union bosses’ self-aggrandizing policy objectives is a familiar phenomenon.

What impact does handing a union monopoly power to deal with your employer on matters concerning your pay, benefits, and work rules have on your pay?

Federal Labor Board has now certified majority decertification vote to end AFT union officials’ “representation” at KIPP Charter High School