Compulsory Unionism ‘Fundamentally Wrong’

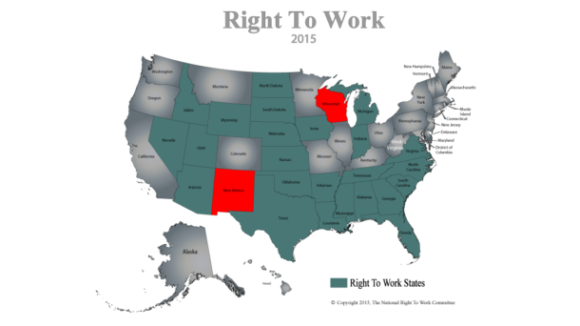

Right to Work Legislation Proliferates Across The Land (Source: February 2015 National Right to…

As readers can ascertain just from the hyperlinked headline below, an editorial appearing in the Albuquerque Journal yesterday doesn’t make for pleasant reading. But it does add to the mountain of evidence that former New Mexico Democratic Gov. Bill Richardson ill-served his state a little more than a decade ago when he signed into law a measure imposing union monopoly bargaining on state and local public servants, including teachers. The Land of Enchantment’s government-sector monopoly-bargaining law has had a detrimental impact on public employees as well as on taxpayers.

As the Journal editorial reports, in 2012 Bernalillo County (which is located in the Albuquerque metropolitan area) agreed to a nearly $1 million settlement with three female Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC) inmates who had accused MDC guard Torry Chambers of rape. Nevertheless, today Chambers is still on the MDC payroll and still “gets a paycheck courtesy of the taxpayers.”

Recently, more than three years after the original accusations were made, Chambers was indicted on eight counts of rape.

The county did try to move Chambers out of his job in 2011. But it failed, and it is not likely to succeed in getting him off the MDC payroll even now that he has been indicted. The reason is the zealous opposition of officers of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME/AFL-CIO) union.

Wielding the monopoly-bargaining power they have enjoyed under New Mexico state law since 2003, AFSCME union bosses “successfully filed a grievance, and [Chambers] was moved to an all-male unit where he remained until September 2013.”

At that time, another female inmate accused him of rape, and he was put on paid leave. The MDC wanted to put him on unpaid leave, but failed. The Journal editorial explains that Chambers could not be fired unless he was convicted, and otherwise, under the union contract, he had to be paid:

The union cited a clause in its contract that does not allow for unpaid leave. So, it would seem, moving an accused rapist away from his prey and off the payroll is subject to union negotiations. In 2012 the county allowed Chambers to work in an all-male cell. But after the fourth inmate accused Chambers of rape he was put on paid leave.

The public should be outraged both over how long it took for charges to be brought and because of the conditions under which Chambers is being paid for not working.

Though the Journal editorialists don’t say it, it is also safe to assume that many conscientious MDC employees are outraged by the fact that union officials who purport to “represent” them are using every legal tactic available to ensure that a man who is now set to go on trial for raping inmates and for “helping another inmate to rape fellow MDC inmates” remains on the public payroll for as long as possible. But under New Mexico’s monopoly-bargaining law it is impossible for honest employees to protest the AFSCME bosses’ callous cynicism by withdrawing from the union and representing themselves.

No wonder so many public employees in states where the right not to join a government union remains fully protected want nothing to do with the AFSCME union. Retaining protections for such employees’ Right to Work and extending those protections to employees who are currently conscripted into a union are key objectives of the National Right to Work Committee.

Editorial: Union goes to bat for accused rapist

Right to Work Legislation Proliferates Across The Land (Source: February 2015 National Right to…

About ten minutes apart, the New Mexico House and the Wisconsin Senate passed their respective Right to Work Bills. The New…

From KRQE News 13: Republican State Sen. Sander Rue is proposing the bill which would bar unions from forcing workers to…