Will Team Biden Weaponize Workers’ Pensions?

Big Labor abuse of worker pension and benefit funds as a means of advancing union bosses’ self-aggrandizing policy objectives is a familiar phenomenon.

[vsw id=”rYk_DXHykTI” source=”youtube” width=”560″ height=”325″ autoplay=”yes”]

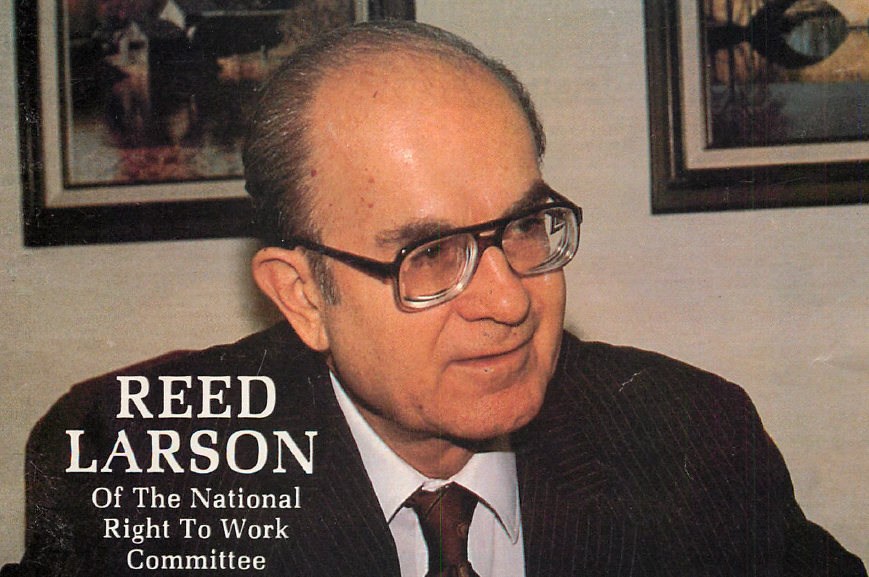

(Mr. Reed E. Larson passed away late Saturday, September 17, 2016)

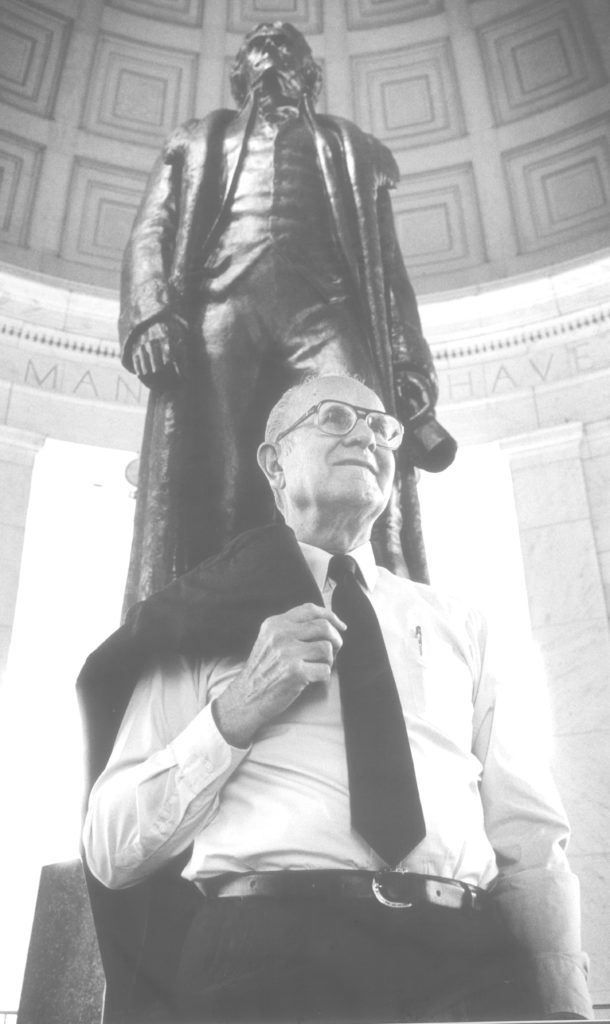

After a visit to the United States, a noted British journalist wrote a column in the London Daily Telegraph about the Right to Work movement. National Ri ght to Work Committee President Reed Larson, the journalist wrote, is “the man that American trade union bosses most love to hate.” It was a tribute, not based on passion, but on the solid record of accomplishments chalked up by the National Right to Work Committee under Larson’s leadership.

ght to Work Committee President Reed Larson, the journalist wrote, is “the man that American trade union bosses most love to hate.” It was a tribute, not based on passion, but on the solid record of accomplishments chalked up by the National Right to Work Committee under Larson’s leadership.

Under the leadership of Reed Larson in 1976, the National Right to Work Committee was given the lion’s share of the credit for securing the President’s veto of legislation that would have legalized coercive union picketing on construction job sites … a remarkable achievement since the Secretary of Labor backed the bill, the full AFL-CIO lobbying apparatus was behind it, the House and Senate approved the legislation almost routinely, and the President previously promised to sign it when it reached his desk.

But instead he vetoed it, after the Right to Work Committee helped turn the issue into a cause celebre and the President was inundated with some 700,000 letters of protest from concerned citizens across the country.

Business Week reported a few weeks after the veto, “Unions [bosses] generally were outraged because they felt the veto indicated a capitulation by the President to the National Right to Work Committee, which organized the successful . . . campaign against the bill.” Congressional Quarterly, a political journal went one better, calling the successful Right to Work effort “one of the most intensive lobbying campaigns of the year.”

What the Right to Work Committee did, complained the AFL-CIO News, was to “shift … the debate to issues of ‘individual freedom’ and ‘coercive’ unionism.”

Nevada Senator Paul Laxalt commented on Mr. Larson’s organization, “Now I know just what a dedicated and professional performance really is.”

It is this dedication and professionalism infused by Mr. Larson that helped turn the once little Right to Work Committee into not only one of the most influential, but one of the largest public interest groups in the country.

As the Washington Post wrote in a front-page story headlined Big Labor Finds Tough Opponent: “This once-tiny organization … has grown into a mass political body with 300,000 [now 2.8 million] members (Common Cause has 265,000), an extraordinarily effective public relations division, and a growing appetite for combat with organized labor … Reed Larson … the dominant figure in the Right to Work movement … has guided the Right to Work Committee and its affiliated groups from a status of fledglings to a prosperous and expansive adulthood. He began in 1959 with a handful of employees, and now has 85. The budget was once measured in thousands; last year the Committee spent $4.5 million; the Foundation which supports lawsuits, nearly $3 million.”

The Article even refers Larson as “anti-establishment” before anti-establishment became cool.

The “common situs” victory, of course, was not the first time the Right to Work Committee went up against Big Labor and emerged the victor.

Earlier achievements of the National Right to Work Committee, under Larson’s direction, include the successful defense of Section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley Act against repeal in 1965 and 1966. Section 14(b) is the provision of federal law which authorizes state Right to Work laws banning forced union membership. Over half of the states now have these laws, the most recent addition being West Virginia, which passed its law during the summer of 2016.

In 1970, the National Right to Work Committee was triumphed again against a combined effort of the AFL-CIO and the Nixon Administration to enact a law authorizing compulsory unionism in the Postal Service. Instead, Congress reacted to the public outcry generated by Mr. Larson’s Committee by including a strict Right to Work provision in the then-new Postal Reorganization Act.

Realizing that fighting legislative battles was not enough, Mr. Larson founded the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation in 1968 to provide free legal representation in the courts to help workers exercise their Right to Work. The Foundation has represented hundreds of thousands of workers in precedent-setting lawsuits. To date, Foundation attorneys argued seventeen cases to the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of individual workers.

Reed. E. Larson Biographical Details

Mr. Larson passed away peacefully late in the evening on Saturday, September 17. Mr. Larson’s beloved wife, the former Jeanne Hess, had passed away in 2010. Larson is survived by their three daughters, and by nine grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

Reed Eugene Larson was born in Agra, Kansas on September 27, 1922. Larson received an Electrical Engineering degree from Kansas State in 1947, and pursued an engineering career for some seven years at the Coleman Company in Wichita. In 1947, he married (Marjorie) Jeanne Hess of El Dorado, Kansas.

He graduated from Agra High School in 1940 and joined the Army as a Second Lieutenant in 1943.

After serving in the war effort, Mr. Larson returned to Kansas. In 1947, he completed his Electrical Engineering degree from Kansas State University. In 1948 (after briefly working for Stein Laboratories in Atchison, Kan.), he accepted a position in the engineering department at Coleman Company in Wichita.

He immediately became active in his community, joining the Wichita Junior Chamber of Commerce. He was active in Jaycees, serving as President of the Wichita Jaycees in 1952 and 1953. President of the Kansas State Jaycees in 1953 and 1954, and in 1956 was honored by the national Jaycee organization as “outstanding national chairman.”

Following the war, what came to be known as “forced dues” contracts, as well as, rampant union strike line violence, and other excesses committed by union officials sparked a public backlash across the nation.

In 1947, Congress enacted reform legislation known as the Taft-Hartley Act. Instead of repealing the forced dues sections entirely, Section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley instead provided a specific “escape hatch” from federally- imposed forced dues authorizations. NLRA Section 14(b) created a federal affirmation that state legislatures and electorates may enact Right to Work laws and block the NLRA’s default federal imposition of forced dues. Under Section 14(b), state Right to Work laws effectively prohibit union officials in most private sector industries from requiring workers to pay union dues in order to get or keep a job.

Opposition to compulsory unionism ran strong in Kansas where Reed Larson became an active leader in the Topeka area effort to build support for the state Right to Work legislation.. The Coleman Company granted Mr. Larson a six months leave allowing Mr. Larson to devote himself fulltime to mobilizing support for a Kansas Right to Work law. In 1954, he was named the executive vice president of the new Kansans for Right to Work. Mr. Larson often remarked that those six months stretched into four years, then 50.

Mr. Larson’s efforts bore fruit in 1955 when the Kansas Legislature passed a Right to Work law, however Governor Fred Hall vetoed the measure.

In 1958, national grassroots anger over forced unionism triggered statewide initiatives in six states (including Kansas lead by Mr. Larson) to enact Right to Work by the vote of the people.

However, ballot initiatives proved to be a bad strategy and a setback for the Right to Work movement. Fueled with millions of dollars in forced union dues, local Right to Work supporters in the states were overwhelmingly outspent. Five out of six statewide votes on Right to Work proposals went down to defeat.

The only one bright spot – Kansas, where the Right to Work ballot measure won under Mr. Larson’s guidance. Across the United States, Right to Work proponents nationally were in disarray. So, the leaders of the newly organized National Right to Work reached out to Reed Larson and asked him to head up the fledgling organization as their first Executive Vice President.

Mr. Larson’s first major battle as the National Right to Work Committee leader came during the 1964 elections. Concerns that Nelson Rockefeller’s and Lyndon Johnson’s ties to Organized Labor could imperil Right to Work and Section 14(b), Reed Larson backed Barry Goldwater in 1964. It was a move that nearly cost him his job. Liberal members of the National Right to Work Committee Board – including businessman Richard Snelling, a future Vermont Governor – narrowly lost their bid to fire him. The vote was so close that one ailing board member had to be carried to the meeting on a stretcher in case he would be needed to cast the deciding vote.

But, as Mr. Larson predicted, President Johnson – backed up by majorities in both houses of Congress – demanded immediate repeal of Section 14(b) in an attempt to wipe out all state Right to Work laws. Reed persuaded then-Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen to launch a Mr. Smith Goes to Washington-style filibuster in the U.S. Senate, handing Johnson an historic legislative defeat. A political cartoonist at the time drew the battle with Reed Larson as a scrawny young David swinging a sling and slaying an enormous Big Labor Goliath.

In 1969 and 1970, Mr. Larson took on President Nixon, the Chamber of Commerce, and the AFL-CIO who were seeking to unionize the Post Office and require letter-carriers to pay union dues in order to work for the “U.S. Postal Service.” Since the NRTW organization depended almost entirely upon contributions received through the millions of pieces of mail it mailed annually, fighting postal union bosses was a particularly bold action.

Two of Reed Larson’s better known political victories came from his roles in defeating President Jimmy Carter’s attempts to pass a federal law imposing forced unionism on state and local government employees and to enact a lopsidedly pro-union “Labor Law Reform” bill which was widely seen as a shameless political payoff for Organized Labor’s record breaking forced-dues fueled support during the 1976 election cycle.

It was during these battles that National Right to Work, under Reed Larson’s direction, began to pioneer the use of direct mail to carefully targeted lists mobilizing grassroots pressure on Capitol Hill. The AFL-CIO was so caught off guard that it produced a big budget movie called the “Right-Wing Machine” to “expose” the Committee’s sophisticated direct mail program.

Key to the victories in the 1970s were computer-generated letters to individual citizens quickly warning them about union-supported legislation and enclosing up to six pre-addressed postcards for them to stamp and mail to their Congressmen and Senators before these bills could be passed. At one point during a come-from-behind Labor Law Reform battle, Reed Larson’s National Right to Work Committee mailed over 10 million such letters in a single day. On another occasion, the National Right to Work Committee bought up most of the available post-card paper stock east of the Mississippi. Forced by the Committee’s voluminous mail program, the United States Postal Service granted the National Right to Work Committee its own zip code.

After winning these “unwinnable” legislative fights in Congress, Reed Larson turned the Committee’s guns on Congressmen and Senators who had voted for either of Carter’s legislative initiatives, or Big Labor’s “Common Situs Picketing” scheme, which had nearly become law during the Ford Administration. Union bosses lost a lot of “friends” in Congress as many forced-dues-backed politicians went down to defeat in the 1978 and 1980 elections.

Mr. Larson had supported Ronald Reagan in the 1976 and 1980 primaries, and was a frequent guest and advisor at the White House following the former union president’s election. Mr. Larson publicly applauded President Reagan’s resolve in enforcing the ban on federal employee union bosses ordered strikes like the famous 1981 federal air traffic controller’s strike.

Internationally, Mr. Larson made his mark as well. Mr. Larson consulted with a little-known British Member of Parliament named Margaret Thatcher and eventual Prime Minister, providing advice on numerous issues such as taking on the United Kingdom’s immensely powerful union chiefs.

In the U.S., House Speaker Tip O’Neill maintained his grip on the House of Representatives and the Democrats retook the Senate in 1982. They joined with a faction of Republicans led by New York Congressman Jack Kemp in seeking to enact so-called “anti-doublebreasting” legislation, essentially a repackaging of the failed decades-old “common situs legislation” power grab. Mr. Larson successfully branded the measure as the Construction Forced Unionism Bill, and the National Right to Work Committee was publicly credited with ensuring its defeat.

Following the National Right to Work Foundation’s 1988 landmark Beck decision, in which the Supreme Court ruled that non-union workers could no longer be required to financially support political and ideological stands taken by union officers as a condition of employment, Mr. Larson launched a national campaign to pressure President George H. W. Bush to issue an Executive Order notifying workers of their newly-granted rights. Eventually, Mr. Larson was invited to join President Bush in the Rose Garden for the Bush’s Beck Executive Order signing ceremony.

The National Right to Work Committee, under Reed Larson’s leadership, was credited with helping to defeat Big Labor’s Pushbutton Strike bill, also called the “anti-striker replacement” bill, spearheaded by President Clinton and U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy.

And in 1996, for the first time in history, the U.S. Senate held a recorded vote on National Right to Work legislation – which would have repealed the portions of federal law which authorize union officials to impose compulsory union dues.

Reed Larson was a dedicated Rotarian as well as an active member of his Baptist church where he helped organize a major capital building campaign and shared the pews with close family friends including fellow-Kansan Senator Bob Dole and Right to Work stalwart Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina.

In 2003, Reed Larson announced that he would be stepping down from day-to-day duties managing the Committee and Foundation as President and recommended his longtime Vice President, Senior Vice President, and Executive Vice President Mark Mix as his successor. The Board of Directors concurred.

A few years later, Reed and Jeanne Larson relocated to Williamsburg, Virginia. Mrs. Larson died in 2010. Mr. Larson continued to commute from their home in Williamsburg to his office at the national headquarters in Springfield, Virginia weekly and continued to work three days a week as an ex-officio director. Mr. Larson moved to Seattle, Washington to be closer to his daughter and grandchildren.

Big Labor abuse of worker pension and benefit funds as a means of advancing union bosses’ self-aggrandizing policy objectives is a familiar phenomenon.

What impact does handing a union monopoly power to deal with your employer on matters concerning your pay, benefits, and work rules have on your pay?

Brief challenges Labor Board’s attempt to expand coercive, anti-employee organizing scheme