Is This Any Way to Run a City’s Schools?

Leaked CTU Proposals Won’t Do Anything to Improve Schools’ Poor Performance

‘Impossible’ Victory Was Made Possible by Grass-Roots Activism

(Click here to download the June 2015 National Right to Work Newsletter)

(Click here to download the June 2015 National Right to Work Newsletter)

Next month marks the 50th anniversary of the 221-203 vote in the U.S. House of Representatives to rubber-stamp union-label Congressman Frank Thompson’s (D-N.J.) H.R.77, legislation to “repeal Section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley Act.”

Since Section 14(b) is the sole provision in any federal labor statute that explicitly authorizes states and territories to prohibit forced union membership, adoption of H.R.77 would have destroyed Right to Work protections for employees nationwide.

Many supporters of state Right to Work laws, then 19 in number, were discouraged by the July 28, 1965 roll call because they correctly judged that Big Labor’s grip over the U.S. Senate was even tighter than its hold on the House.

Public Opinion Backed 14(b) – Most Senators Didn’t Care

Indeed, there was very little chance of getting enough support to defeat H.R.77 in an up-or-down Senate vote.

Public opinion wasn’t the problem. A nationwide scientific poll of the U.S. adult population had recently shown that the American people favored retention of Section 14(b) by better than a two-to-one margin.

But National Right to Work Committee members and officers, who were spearheading the campaign to save Section 14(b), knew from the start that persuading a majority of senators to vote in accord with the wishes of their constituents would be virtually impossible.

For 14(b) to survive, Right to Work activists would have to persuade a determined minority of senators to band together in an extended debate that would prevent H.R.77 from coming to a final vote.

‘I Must Say That There Is Much More Support For 14(b) Than I Had Realized’

At the time, if the entire chamber was present, 34 out of 100 senators could defeat a “cloture motion” and keep a debate going indefinitely.

Of course, the extended-debate strategy could succeed only if a respected senator was willing to lead the troops.

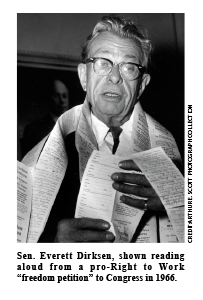

And Committee officers were convinced that Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-Ill.) was the only member of the chamber capable of holding together for as long as it was necessary to prevail a pro-Right to Work coalition of otherwise disparate interests and perspectives.

But when first pressed by Committee Executive Vice President Reed Larson to lead an extended debate against H.R.77, Mr. Dirksen demurred. He contended grass-roots opposition wasn’t strong enough. He did not want to invest his credibility in a “lost cause.”

A week later, Mr. Larson returned to Capitol Hill armed with copies of more than 3000 pro-14(b) editorials, representing the opinions of more than 1500 daily newspapers and more than 1000 weeklies, based in every part of the country and ranging across the political spectrum.

Mr. Dirksen was impressed: “I must say that there is much more support for 14(b) than I had realized.” He finally agreed to lead the extend debate after Committee legislative staff recruited six other senators, three from each party, to serve as lieutenants in the battle to stop H.R.77.

In the late summer and early fall of 1965, grass-roots Right to Work supporters inundated Senate offices with mail and phone calls insisting that 14(b) be preserved. The message got through.

‘[T]here Is No Amicable Compromise Possible’

On October 11, union bosses were flabbergasted when a motion to cut off debate so H.R.77 could be rubber-stamped received just 49 votes, far fewer than the 67 needed.

Big Labor Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Mont.) pulled the bill from the floor that month, but brought it back in January 1966, evidently hoping the furor had died down.

Mr. Dirksen immediately assured him it hadn’t: “We will fight to the end. And there is no amicable compromise possible. There is no sweetener for 14(b).”

In February 1966, after two more failed cloture votes, Mr. Mansfield finally threw in the towel.

This article concludes a two-part series recalling the 1965-66 battle to save 14(b). The first installment appeared in the May Newsletter.

Leaked CTU Proposals Won’t Do Anything to Improve Schools’ Poor Performance

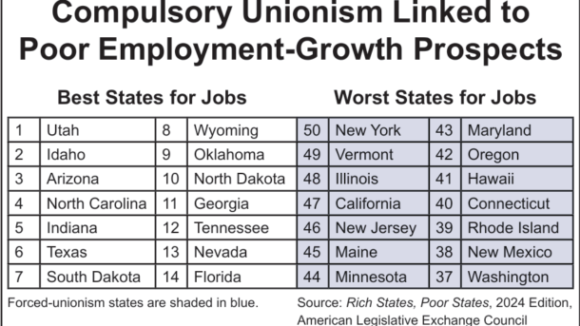

Wherever Big Labor wields the power to collect forced union dues, union bosses funnel a large share of the confiscated money into efforts to elect and reelect business-bashing politicians. Employment growth tends to lag as a consequence.

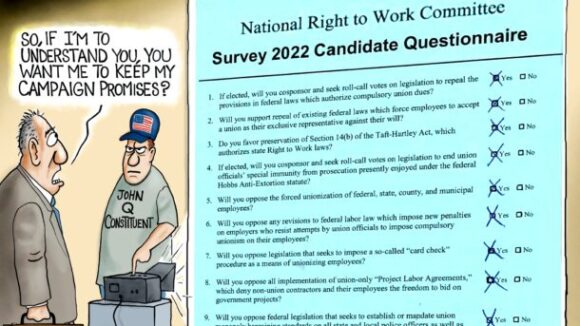

Members Insist They Keep Pro-Right to Work Campaign Promises