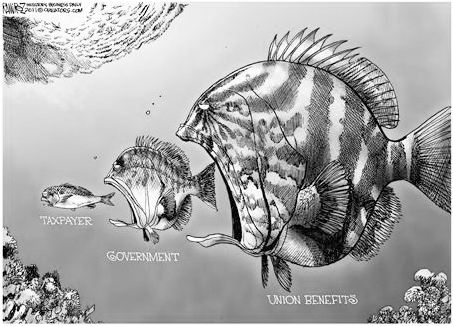

The Government Workers Union Albatross

Phillip K. Howard examines how union bosses for government workers are fleecing the taxpayers: The indictment of seven Long Island Rail Road workers for disability fraud last week cast a spotlight on a troubled government agency. Until recently, over 90% of LIRR workers retired with a disability—even those who worked desk jobs—adding about $36,000 to their annual pensions. The cost to New York taxpayers over the past decade was $300 million. As one investigator put it, fraud of this kind "became a culture of sorts among the LIRR workers, who took to gathering in doctor's waiting rooms bragging to each [other] about their disabilities while simultaneously talking about their golf game." How could almost every employee think fraud was the right thing to do? The LIRR disability epidemic is hardly unique—82% of senior California state troopers are "disabled" in their last year before retirement. Pension abuses are so common—for example, "spiking" pensions with excess overtime in the last year of employment—that they're taken for granted. Governors in Wisconsin and Ohio this year have led well-publicized showdowns with public unions. Union leaders argue they are "decimat[ing] the collective bargaining rights of public employees." What are these so-called "rights"? The dispute has focused on rich benefit packages that are drowning public budgets. Far more important is the lack of productivity. "I've never seen anyone terminated for incompetence," observed a long-time human relations official in New York City. In Cincinnati, police personnel records must be expunged every few years—making periodic misconduct essentially unaccountable. Over the past decade, Los Angeles succeeded in firing five teachers (out of 33,000), at a cost of $3.5 million. Collective-bargaining rights have made government virtually unmanageable. Promotions, reassignments and layoffs are dictated by rigid rules, without any opportunity for managerial judgment. In 2010, shortly after receiving an award as best first-year teacher in Wisconsin, Megan Sampson had to be let go under "last in, first out" provisions of the union contract. Even what task someone should do on a given day is subject to detailed rules. Last year, when a virus disabled two computers in a shared federal office in Washington, D.C., the IT technician fixed one but said he was unable to fix the other because it wasn't listed on his form. Making things work better is an affront to union prerogatives. The refuse-collection union in Toledo sued when the city proposed consolidating garbage collection with the surrounding county. (Toledo ended up making a cash settlement.) In Wisconsin, when budget cuts eliminated funding to mow the grass along the roads, the union sued to stop the county executive from giving the job to inmates.