Multinational corporations have a new ally in their battles with organized labor: unionized workers.

As organized labor loses leverage in a race-to-the-bottom global market, some workers are becoming so disillusioned by what their unions can, or rather can’t, do for them that they want out. The disaffected include dozens of machinists at Caterpillar Inc.’s plant in Joliet who crossed the picket line during a strike last summer and are planning unfair labor practices complaints against the union.

Organized labor’s slippage is most acute in the manufacturing sector, which has lost 4.7 million jobs and seen membership shrink by almost a third since 2001, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Overall, private-sector union membership stands at just 6.9 percent nationally and 10.6 percent in Illinois.

“Unions lack sufficient power to get their way,” says Mike Zimmer, a law professor at Loyola University Chicago. “It is a period of concession bargaining.”

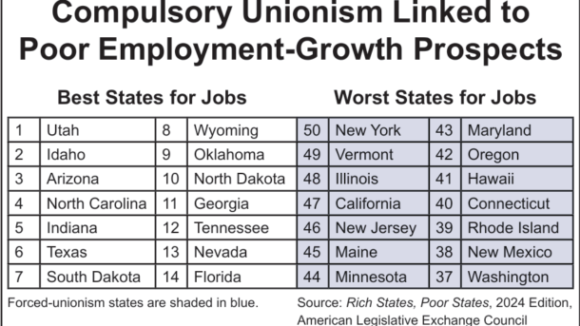

Many rank-and-file employees have opposed unions all along, of course. Despite organizing drives, workers have turned down collective bargaining at automobile plants across the South. Legislatures in 23 states have enacted “right-to-work” laws that allow employees to opt out of dues-paying membership at union shops; Indiana joined this camp early this year.

Now some workers in union-friendly states are turning on their brethren over strikes.

In Kansas City, Mo., a Honeywell Inc. employee filed charges with the National Labor Relations Board this year against an International Association of Machinists local for imposing a $7,361.36 fine for working during a strike, according to the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, an organization backed by businesspeople and individuals who oppose labor contracts mandating membership. In Los Angeles, three employees at a Boeing Co. plant brought complaints against the United Auto Workers in 2010 after it tried to discipline them for refusing to give up their jobs during a strike. The three claimed to have resigned from the union before the walkout.

Similar charges have been filed and settled in Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio, New Jersey and Connecticut, with unions including the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and the United Steelworkers of America named in complaints.

In Illinois, the latest intra-union conflict—and potentially the biggest yet—is in Joliet. Last May, after contract negotiations stalled, nearly 800 IAM-represented employees walked off the job at Caterpillar’s hydraulic-parts factory. After a few weeks, more than 100 returned to work, fed up over the lack of progress in the talks and pinched by the union’s $150-a-week strike pay, some workers say.

When an agreement was reached in mid-August, the contract provided less than the one before it: The IAM gave in to an hourly pay freeze for veteran employees, an end to pensions, a doubling of health care premiums and a one-time ratification bonus of $3,100 instead of $5,000 under the previously proposed pact. The terms were almost identical to a Cat contract ratified by the UAW a year earlier.

Doug Oberhelman, chairman and chief executive of the Peoria-based heavy-equipment maker, acknowledges that the givebacks hurt employees. But, in a recent speech in Chicago, he explained that management compared compensation to factory hands across Illinois and around the world and concluded that to be “market competitive,” Caterpillar had to insist on the concessions.

Cat has earned a reputation for driving a hard bargain with unions. In February, the company closed a locomotive plant in Ontario after workers refused to accept a 50 percent pay cut. In his speech, Mr. Oberhelman emphasized that management sited Caterpillar’s two newest U.S. plants in Georgia and Texas, which are right-to-work states.

But rather than blame the boss, some workers are directing their anger toward a union that they say is out of touch with current realities and refuses to acknowledge its limited power.

“They are not effective,” says Steven Olson, 54, a former IAM member who crossed the picket line last summer. “With high unemployment and companies willing to relocate, you just don’t have the options that you did 30 years ago. The whole world has changed.”

This month, Mr. Olson and another Caterpillar worker filed an unfair labor practices charge against the union local with the help of the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, saying it’s illegal to punish them for returning to work. Mark Mix, president of the foundation, says 61 other Caterpillar workers who also crossed the picket line have called the organization looking to lodge similar complaints. “I suspect we will have some more charges here shortly,” he says.

Steve Jones, an official of the IAM union local that represents workers at the Joliet factory, says he understood that workers need to provide for their families, which meant crossing the picket line. But he adds: “We don’t negotiate for individuals; we negotiate for the benefit of the group.”

In the past, hard times often drove people toward collective bargaining as they sought strength in numbers. Today, though, labor experts foresee more workers turning against organized labor. In a global economy, unions increasingly seem impotent, the experts say, because jobs can be done elsewhere, often for less money.

“The longer workers are on strike and the harder the economic conditions are, you’re going to have some dissentions and some defectors,” says Robert Bruno, a professor of labor and employment relations at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

“Workers in each country are really now competing with workers all around the world,” Loyola’s Mr. Zimmer says.