Will Team Biden Weaponize Workers’ Pensions?

Big Labor abuse of worker pension and benefit funds as a means of advancing union bosses’ self-aggrandizing policy objectives is a familiar phenomenon.

The Wall Street Journal’s Paul Gigot, Dan Henninger, James Freeman, Dorothy Rabinowitz, Kim Strassel and Collin Levy discuss the individual freedom and business opportunities that Indiana’s Right to Work bills bring to the Hoosier state:

The Wall Street Journal’s Paul Gigot, Dan Henninger, James Freeman, Dorothy Rabinowitz, Kim Strassel and Collin Levy discuss the individual freedom and business opportunities that Indiana’s Right to Work bills bring to the Hoosier state:

Gigot: The first big labor fight of the year is taking shape in the Hoosier State. How Indiana’s right-to-work push could change the political and economic landscape in the Midwest.

Gov. Mitch Daniels: The idea that no worker should be forced to pay union dues as a condition of keeping a job is simple and just. But the benefits in new jobs would be large. A third or more of growing or relocating businesses will not consider a state that does not provide workers this protection.

Gigot: He was reportedly booed by protesters in the statehouse hallways for those remarks in his annual State of the State Address this week, but Gov. Mitch Daniels is hoping to make Indiana the first state in more than a decade to approve right-to-work legislation. It would allow individual workers to decide if they want to join a union and ban contracts that require nonunion members to pay dues once their work site is organized. Republican leaders in the state have made it their top legislative priority this year, but Democrats and their union allies aren’t giving up without a fight.

So, Collin, we heard last year, after the brawl in Wisconsin, that somehow this was over for a union reform movement. What’s–why is it happening in Indiana now?

Levy: Well, I mean, I think it is a really interesting situation you see happening in Indiana, because Indiana’s this sort of industrial state of the Midwest. And you have a particular situation now where Indiana is poised to achieve enormous competitive advantages over states in the Midwest like Michigan, like Illinois. These are high-taxed, unionized states. And Gov. Daniels has taken this moment to say, “You know, we’ve already made sort of some significant gains in terms of improving the business climate here. We saw what happened in Wisconsin. But, look, you know, we have an opportunity to lure an awful lot of businesses here if we can make it clear that workers can act as free agents,” you know? Unions are portraying this as a radical change, but it’s really just about worker freedom.

Gigot: Kim, the nearest right-to-work state in the Midwest is Iowa. So how much economic benefit could there be here, really, when you get down to it, for Indiana?

Strassel: It’s huge. When Mitch Daniels talks about this, he is looking at the South. That is where the epicenter of most right-to-work states have been and where there has been a flood of manufacturers who have moved from the North to the South over recent decades to take advantage of those lower-cost, nonunionized states. And if Indiana could do this, it would be a sort of central pole for people to remain in the Midwest and locate and give an enormous advantage over competitors.

Gigot: The last state to try to do this was New Hampshire, believe it or not, which had elected huge Republican legislative majorities in 2010. Tried to pass right-to-work. They did. It was vetoed by the Democratic governor. Indiana Republicans also have big majorities, and it looks like they are poised to do it.

Henninger: And I hope they do. I mean, I think this is really almost a life-and-death issue for Indiana. Twenty percent of Indiana’s workforce is in manufacturing. That’s the highest percentage in the United States.

Gigot: Wow. Manufacturing is only 11% of the entire U.S. economy.

Henninger: It’s about 20% in Indiana. They make elevators, refrigerators, mobile homes, engines–Cummins Engine is there. They attracted Toyota, they attracted Honda to the state. But if you’re in manufacturing, that’s about half of your costs–labor costs–about half of the total cost of a company. They have got to be competitive with the southern tier of states that we just saw in that map, or those companies will inevitably migrate. There’s a lot of outmigration in Indiana right now. The level of real incomes is falling because all the manufacturing is going to the South. It is a make-or-break deal for Indiana, Paul.

Gigot: Collin, Democrats are trying to play a game of hide-and-seek in Indiana, again trying to go out–leave the state or leave the–not provide a quorum for Republicans to pass this. Is that likely to succeed?

Levy: No, it’s not. And one of the reasons is, if you recall, after the Wisconsin battle last year and the walkout there, you also had about a five-week walkout by Indiana’s Democrats, after which time, Republicans in the Legislature passed a law that said if you’re gone from work for more than three days, guess what, there are consequences. There’s about a thousand-dollar personal fine. So what you’re seeing now are these sort of rolling walkouts, where they’re here for a few days and gone for another day, and so that’s what’s been happening. But I don’t think that that’s going to hold. They–basically, the Democratic leader has acknowledged that this is probably going to go forward.

Gigot: Kim, quickly, what would be the impact nationally, and on the presidential election in 2012, if Indiana passes this?

Strassel: It puts the union issues back in here. And just on the political point, Paul, I want to point out this is different than what happened in Wisconsin. The tough thing for Scott Walker in Wisconsin was union guys could say, “You’re attacking the middle class, taking away benefits.” This is an issue in Indiana that really resonates with Americans that are saying, “Are you going to be forced to join a union and pay dues?” Most Americans don’t agree with that. If Republicans can frame that in a national debate, it definitely helps them.

Big Labor abuse of worker pension and benefit funds as a means of advancing union bosses’ self-aggrandizing policy objectives is a familiar phenomenon.

What impact does handing a union monopoly power to deal with your employer on matters concerning your pay, benefits, and work rules have on your pay?

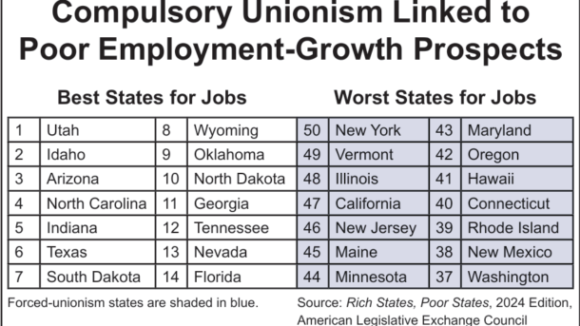

Wherever Big Labor wields the power to collect forced union dues, union bosses funnel a large share of the confiscated money into efforts to elect and reelect business-bashing politicians. Employment growth tends to lag as a consequence.